In 1972, two failed commercial songwriters decided to scrap writing for other people (which wasn’t an overly successful endeavor to begin with) and instead compose and release their own quirky, noodly work as their own. Searching for a name, Walter Becker and Donald Fagen decided on the steam-powered marital aid from William S. Burrough’s Naked Lunch as inspiration, taking the name Steely Dan.

Fagen (keyboards and vocals) and Becker (guitar, bass, and arrangements) enlisted Denny Dias (guitar), Jeff “Skunk” Baxter (guitar), and Jim Hodder (drums) as supporting musicians. Fagen’s relative lack of confidence in his abilities as a frontman led the duo to hire David Palmer to sing lead on at least some songs, especially live.

The group put out Can’t Buy a Thrill that same year, which was a near-instantaneous success based off of “Dirty Work” (with Palmer on lead), “Reelin’ In The years”, and “Do It Again”. The tour that followed allowed Fagen to become more comfortable on stage, leading to a lineup shuffle before the next album Countdown to Ecstacy was released in 1973. Palmer left, leaving the group as a quintet. The album was a victim of the sophomore slump, as the songs were both written and recorded while the band was touring and the repository of killer compositions had evaporated. Although it was successful with songs like “Show Biz Kids”, “Bodhisattva”, and especially “My Old School”, the impact was diminished in comparison to their debut.

In 1974, Steely Dan changed their method of operation slightly, focusing more on studio performance than live events. As a result, they hired more studio musicians, at first for overdubs and additional layers. This irked Jim Hodder, who quickly found himself relegated to backing vocals on a single song after the band used Jim Gordon (formerly of Derek and the Dominos) and Jeff Porcaro (later of Toto) for all of the new album’s drum tracks. Pretzel Logic also featured Chuck Rainey and Wilton Felder on bass in addition to Becker, who transitioned almost entirely to guitar and production.

Buoyed by “Rikki, Don’t Lose That Number” and “Any Major Dude Will Tell You”, the album was seen as a return to form. The ensuing tour led Becker and Fagen to largely eschew live performances, treating them as a necessary evil that distracted the band from their studio adventures. The rest of the band was unhappy with this development, as they were treated as hired guns subject to replacement based on the songwriting duo’s ideas for a given track. Baxter, Dias, and percussionist Royce Jones were out, and the band became a fully studio-centered project. Instead, a murderer’s row of session wizards played the majority of parts.

When most people think of the sound of a typical Steely Dan song, this is the era they think of. The core musicians became Chuck Rainey (bass), Larry Carlton (guitar), Jeff Porcaro (drums), and Michael McDonald (later of the Doobie Brothers with Skunk Baxter) on keyboards and backing vocals. Wilton Felder (bass) and Bernard Purdie (drums) were also regularly featured, as were the backing vocals of Venetta Fields, Clydie King, and Sherlie Matthews. David Paich (keyboards) and Dean Parks (guitar) contributed occasionally. Essentially any first call studio musician based in either Los Angeles or New York was subject to being tapped for Steely Dan sessions.

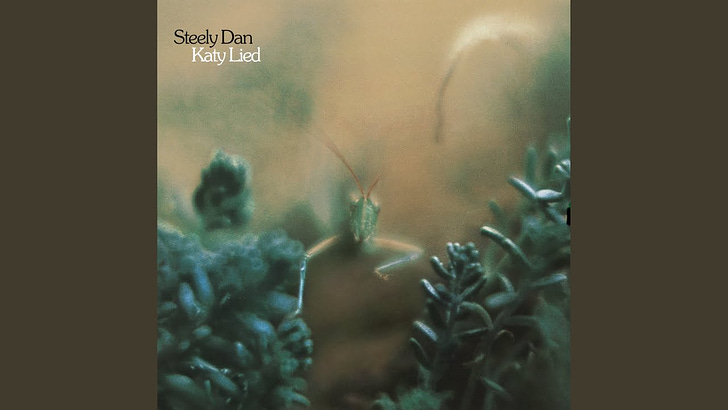

Katy Lied emerged in 1975. Despite the immense attention paid to the recording process, the entire endeavor suffered a major setback when the new digital noise reduction system dbx was used at the mastering stage of production. Both Fagen and Becker thought the system added too much compression and eliminated too much dynamic range, leading them to disavow the album from an artistic standpoint. The album sold well, though, despite their misgivings.

1976 saw the release of The Royal Scam, a continuation on the themes established by the previous two albums. It was not perceived as being as successful either artistically or commercially, but made an impact on the then-nascent radio format of album-oriented rock in which non-single tracks were featured alongside the more prominent singles. The Royal Scam did well in overseas markets for the first time, and the lack of live performances did not diminish its impact at all.

In September of 1977, the crown jewel of Steely Dan’s catalogue was released. Aja leaned even more heavily into jazz idioms, and the roster of session musicians expanded accordingly. Luminaries like Joe Sample, Tom Scott, and Wayne Shorter were enlisted for their expertise. The album was aided by a change in marketing approach, as Becker and Fagan hired manager Irving Azoff for promotions. It didn’t hurt that the album was sold for a lower price than its competition, leading Aja to become one of the first verified platinum albums in America with sales topping one million copies. The recording process earned the group a Grammy for engineering, and nominations for Album of the Year and Best Pop Performance by a Duo or Group. Becker and Fagan toyed with the idea of going out on tour, but dissension amongst the roster of backing musicians in terms of compensation led to abandoning the performances entirely.

Instead, the duo regrouped in late 1978 to begin work on Gaucho. In retrospect, this was a misstep. The band would have been better off with either a longer layoff or a shorter one, as the tension between the two primary songwriters reached a boiling point. Walter Becker’s girlfriend died of a drug overdose in his apartment (amidst his own growing drug problems), and her family sued him for wrongful death. The press coverage was unfavorable and distracted the two from completing the album in a timely fashion. MCA Records bought out their label ABC Records, but there was a dispute as to whether their original record contract was complete or if they could sign with another label. The conflict added to the delay in Gaucho’s release, as did Becker’s injury when he was struck by car in Manhattan.

Gaucho finally came out in 1980, but the damage had been done. Donald Fagen began work on a solo album (The Nightfly), while Becker moved to Hawaii to combat his drug addictions. They had little formal contact until 1986, when they met once more to consider renewing their partnership. The results weren’t what either wanted, so they worked on solo material. Both ended up producing other artists, and they sometimes collaborated with the same musicians on the same projects.

In 1993, Becker produced Fagen’s solo album Kamakiriad, and the duo decided to tour behind the album together for the first time in almost two decades. They collaborated on the release of a box set of all of Steely Dan’s recorded material to that point, then toured those songs for the first time ever. The creative spark returned over the next few years, culminating in 2000’s Two Against Nature (title drop!). Widely seen as a return to form, the album was the most successful of their career both commercially and critically. The album won Album of the Year at the Grammys, beating out the two presumptive winners Radiohead and Eminem. The next year saw them inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame alongside Aerosmith, Paul Simon, Michael Jackson, and Queen.

The duo worked on their next album Everything Must Go until 2003. The process was interrupted by the attacks on the World Trade Center, suspending recording while the New York City studios were unavailable. Once the recording process resumed, they fired Roger Nichols, who had been their engineer for the previous thirty years. No explanation has ever come forward for exactly why this happened. This would prove to be their last album recorded together; touring continued intermittently until 2017.

In 2017, Walter Becker died of esophageal cancer. Donald Fagen signaled his intention to resume touring under the Steely Dan name despite the reservations of Becker’s estate. Lawyers became involved, and the situation remains unresolved. Fagen claims to want to tour under his own name, but promoters insist on using the Steely Dan trademarks for marketing. Whether this is true or not is largely subject to your opinion on the overall honesty and forthrightness of Fagen’s character. I remain unconvinced.

With that, let’s move into my personal top ten Steely Dan songs. As usual, these are my opinions and my opinions alone. No one else can share in either the glory or the blame. I’m considering everything released under the Steely Dan name, so no solo material is eligible, nor are Becker’s collaborations with China Crisis. There’s no prohibition on time period, but I like the “classic” era more, so that’s where the selections come from. And away we go…

10. Black Friday

The noble Fender Rhodes electric piano gets the spotlight here, as played by Donald Fagen. The guitar solo is of note as it is played by Walter Becker himself rather than his studio compatriots. This was the first single off of Katy Lied, and it holds up as well as anything on the album.

9. Do It Again

Early Steely Dan is almost a different band than the one they would become over the years. Denny Dias plays the sitar here in an almost raw, unpolished way that stands out from the other smooth, slick sounds that Fagen and Becker would mature into. For an even less Dannish version, try this one from Waylon Jennings of all people:

8. Aja

One of the most, if not the most, technically demanding songs in the entire Steely Dan catalogue, “Aja” is highlighted by a saxophone solo from Miles Davis veteran Wayne Shorter. Despite its complexity, the song was recorded in rapid fashion. Shorter only took three or four takes, while drummer Steve Gadd completed his parts in only two. The Wiki article goes further in depth about the composition and structure of the song, but it’s clear that “Aja” is complex without sounding forced or contrived.

7. Reelin’ In The Years

Elliott Randall provides the guitar solo that propels this song to greatness, serving as one of the first session wizards to grace a Steely Dan track. Randall was called upon to record additional guitar parts by his childhood friend Skunk Baxter, in addition to Becker and Fagen who had utilized his services when they were staff songwriters with ABC Records. Such luminaries as Jimmy Page (TW:SA) have called this solo their favorite of all time, and it’s certainly a tasty one. Randall was offered a permanent spot in Steely Dan, but declined as he felt that the band wouldn’t last in its then-current incarnation for more than two or three albums. Prescient, no?

6. Black Cow

Chuck Rainey and Joe Sample (late of the Jazz Crusaders with Larry Carlton) are responsible for the inimitable intro to “Black Cow”, with Rainey on bass and Sample on clavinet. Carlton has the guitar parts for the song as well. The opening notes set the tone for the remainder of the album, arguably the group’s best and a cornerstone of the entire yacht rock genre.

5. Bodhisattva

“Bodhisattva” is Steely Dan at their most rocking. There’s an aggression that isn’t necessarily present in their other, more relaxed songs. That isn’t to say that the song is devoid of jazz influence, though. The guitar solos owe just as much to bebop saxophone chromatic scales as Chuck Berry’s (TW:SA) pentatonic Gibson runs. The lyrics are incisive, cutting to the quick on the topic of faux-hippies who eschew materialism but celebrate it just the same. The aping of Eastern concepts of spirituality by those devoid of spirit would become a recurring theme in yacht rock, and Becker and Fagen were at the forefront of that lampooning.

4. Pretzel Logic

If “Bodhisattva” is their most rocking, “Pretzel Logic” is their swampiest and bluesiest song. The shuffling rhythm from Jim Gordon is deceptively tricky, with cymbal accents in places you wouldn’t expect and ghost notes scattered like wildflower seeds on the prairie. Steely Dan gets a (sometimes well-deserved) reputation as a clinical and austere band, but “Pretzel Logic” is as down and dirty a song as any other early Seventies blues-rock band could muster. Take, for instance, this cover by blues-rock maven Warren Haynes:

3. Dirty Work

One of just two Steely Dan songs with David Palmer as the lead vocalist, “Dirty Work” is the most pop they ever sounded. The horn section of Jerome Richardson on saxophone and Snooky Young on flugelhorn provides the counterpoint to Fagen’s Wurlitzer and organ work. Don’t be fooled by the benign tone struck by the combination of Palmer’s smooth vocal and the gentility of the melody; these lyrics are outright hostile, representing regret at an adulterous affair.

2. Deacon Blues

Bernard “Pretty” Purdie was the regular drummer for later Steely Dan songs, and his snappy snare is the foundation of “Deacon Blues”. The horn parts (arranged by Tom Scott of the L.A. Express and the Blues Brothers Band in addition to countless sessions) glide over the bedrock bassline from Becker. The tenor saxophone solo from Pete Gottlieb of the Tonight Show Band is effortless and airy. Lyrically, the Walter Mitty-esque protagonist is ready to throw his comfortable but dreary life away to pursue his dream of becoming a jazz musician, but the narrative implies his dreams are doomed to fruitlessness.

1. Kid Charlemagne

Every portion of this song is magnificent. Starting from the bottom, there’s Pretty Purdie’s shuffle, although not his more well-known “Purdie Shuffle” that’s featured on “Home at Last” and “Babylon Sisters”. Don Grolnick on Fender Rhodes, Paul Griffin on clavinet, and Fagen on organ are in lockstep with the bassline from stalwart Chuck Rainey. The backing vocals from the usual complement of harmonists (Venetta Fields, Clydie King, and Sherlie Matthews, plus Michael McDonald) are stellar. Becker’s rhythm guitar is the counterpoint for Larry Carlton’s stunning lead. Entire theses have been written about the solo and its influence on guitar since. Carlton himself said that it was the defining work of his career. The lyrics tell one of the most complete stories in the Steely Dan songbook, detailing the rise and fall of amateur pharmaceuticalist Owsley Stanley (architect of the Grateful Dead’s Wall of Sound). The denouement of the song is Stanley’s arrest, immortalized from the other side by “Truckin’”. In reality, the song is about the death of the hippie mentality and its metamorphosis into the yuppie of the Eighties. Steely Dan was merely the most notable in articulating the fall and rise of the mindset.

Love this post. Wolf Eyes' cosigning on Steely Dan has I think brought them a cache of "coolness" that had long eluded them in the indie scene and made it okay to vocalize liking it. Lyrically, they're a sort of perfect band for people like me (men entering middle age, slightly (but not fully) disenchanted by the events around them) and I am willing more than ever to admit that in spite of how corny it may make me.