Miles Runs the Voodoo Down

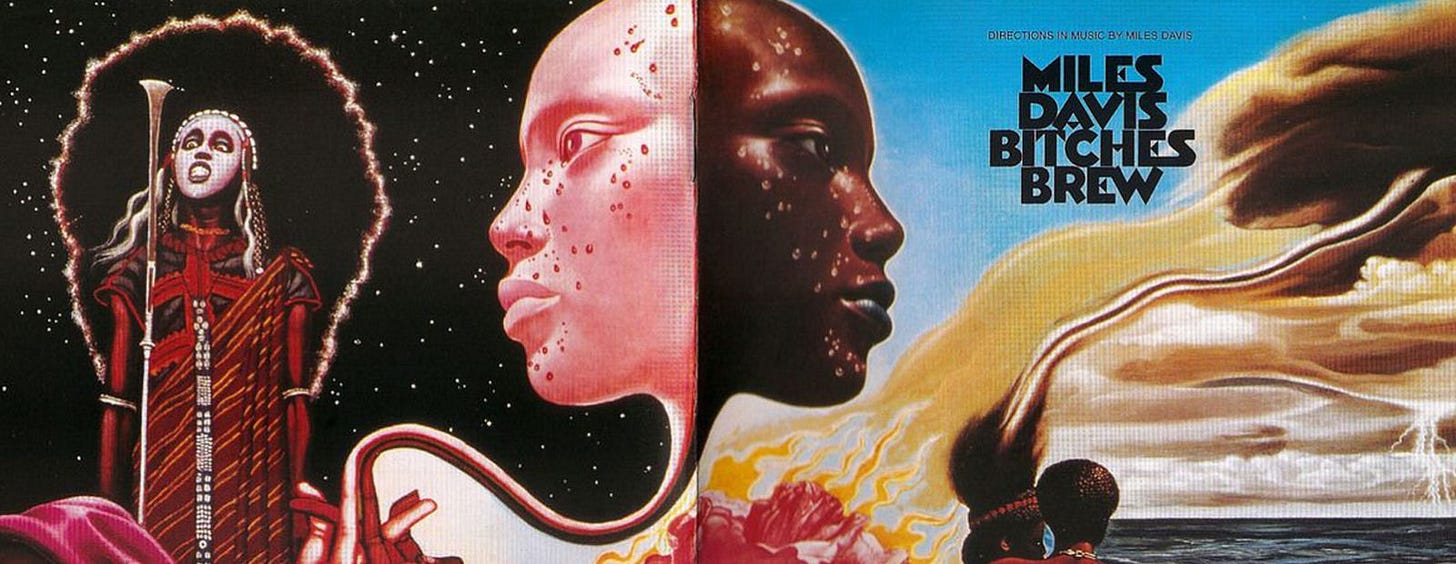

a track by track rundown (see what I did there?) of miles davis' bitches brew in conjunction with a capsule history of one of jazz's greatest artists.

Three days in the summer of 1969 changed music forever. No, I’m not talking about Woodstock; get your head out of your hindquarters. Woodstock was held on August 15th through the 18th on a farm in upstate New York, but the real magic happened on the next three days in New York City. In the Columbia 52nd Street studios, producer Teo Macero assembled a crew of the finest jazz musicians available to work with the legendary Miles Davis on some new material.

Miles Dewey Davis III, born in 1926 and a product of East St. Louis, had already redefined modern jazz twice over. He began playing the trumpet at the age of nine, and within a few short years music consumed his life. At thirteen he joined both a series of local jazz bands and his school marching band; the combination of practical and academic education would prove fruitful. Even before graduating, Davis had sat in with touring bands, going so far as to be offered a permanent spot in Tiny Bradshaw’s outfit. (His mother forbade him from leaving school, insisting that he finish his education before striking out on his own.) Around the time he received his diploma, Davis played a two week engagement with Billy Eckstine’s band at Club Riviera in St. Louis. This was Davis’ first exposure to such jazz luminaries as Charlie “Bird” Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, and Art Blakey, and he realized he could hang with them. Despite his family’s misgivings, Davis was insistent that he needed to abandon plans to attend Fisk University and instead go to Julliard in New York City.

Davis passed the entrance exams with ease, thanks to his formal music education and independent study with orchestral musicians. He was appreciative of the technical aspects of Julliard’s instruction, but disdained the focus on European classical music. Davis would spend most of his time at Julliard playing jam sessions in Harlem with Parker, Thelonious Monk, and Coleman Hawkins. Eventually, he decided that he had learned enough that further education would detract from his creativity and spontaneity, dropping out after less than two years.

By this time, Davis was working full time as a sideman and a bandleader in his own right, with the ever evolving membership in his band usually aligning with the variations in their name: the Miles Davis All-Stars (a quintet), the Miles Davis Sextet, the Miles Davis Nonet, and finally the longest lasting configuration in the Miles Davis Quintet. In East St. Louis, he had acted as musical director for Eddie Randle’s Blue Devils, an experience that taught him how to manage a touring musical act and how to handle the often fragile temperaments of other creatives. The inherent stress in corralling musicians meant that Davis would frequently join other groups as a member instead of a leader, taking a backseat to other gifted talents.

Davis’ longest relationship as a band member was with Parker’s quintet. At the outset of Davis’ musical career, Bird was the guiding light for how Davis viewed jazz. Bird was even Davis’ roommate when he moved to New York for the first time as a Julliard student. However, their relationship became strained after Parker’s substance abuse grew into a pervasive problem, affecting the commercial viability of the group and the quality of their performances. At this point in his life, Davis abstained from drugs and alcohol, and was a committed vegetarian. Davis returned to his own Nonet, exploring more esoteric textures and incorporating distinctly un-jazz instruments like the French horn and the tuba into his arrangements. Discontent to limit himself in any way, he also worked as a sideman in a number of more traditionally aimed groups like Tadd Dameron’s quintet, and began pushing the bounds of bebop (characterized by fast tempos and complex multilayered rhythms) into what would become hard bop, slowing down and simplifying arrangements to streamline for the listener.

Part of Davis’ drive was due to his growing family. He and his girlfriend had three children (Cheryl, Gregory, and Miles IV) by the time 1950 rolled around, and the itinerant lifestyle of a travelling musician was hard on them. To make matters worse for his domestic life, Davis (who was just twenty-four years old) began using heroin, soon to be accompanied by addictions to alcohol and cocaine. His health waxed and waned throughout his life, with some claiming he suffered from sickle cell anemia that spurred near-constant pain. Davis was arrested for heroin possession in 1950, but would be acquitted shortly thereafter; DownBeat magazine covered the arrest, leading to a downturn in opportunities with “straight” groups.

Davis recorded his first album The New Sounds in 1951, a release in the relatively short-lived ten inch format. (If you ever wondered where the Aerosmith song title came from, now you know.) Saxophonist Sonny Rollins and drummer Art Blakey were recruited for the session, both making their names as individuals rather than sidemen. Rollins was in-between stints in prison, first for robbery then for heroin possession himself; he would go on to become one of the first prominent methadone patients and recover completely. Blakey would subsequently form the Jazz Messengers, one of the leading proponents of hard bop jazz that was incubated with Davis.

The next several years were a blur, with Davis descending into the depths of addiction. In order to support his habit, he began acting as a pimp, profiting off of prostitution. He left New York in an attempt to curtail his drug use, moving back in with his father in St. Louis and then to Detroit; he believed removing himself from the big city where heroin was readily available would do him some good. It wasn’t until 1954 that he returned to New York, clean from heroin and ready to record more new music. Davis’ tastes had turned completely from bebop to hard bop.

Whether it was the recovery from addiction, the change in scenery, or continuing health issues, this period of Davis’ life is where his legendary reputation as a curmudgeonly, cantankerous, and contemptuous figure was cemented. Davis claimed that Sugar Ray Robinson’s perceived arrogance gave him the freedom to express himself fully; he believed that someone at the top of their field didn’t have to bother with niceties or politeness. Davis would pick fights with critics, come to blows with bandmates, and be downright abusive to his romantic partners. Simply put, Miles Davis was not a nice person in any way, shape, or form. Whether his talent justified that behavior is a quandary best left to the ethicists. (Just kidding, it emphatically does not.)

For the next twenty or so years of his career, keeping track of all of Miles Davis’ recordings and bandmates is a monumental task. Davis would shift from one group to another constantly, bouncing back and forth between styles and genres with stunning adroitness. In the span of a single month he could be working for three or four different record companies, in bands as small as a trio and as large as an orchestra. I will attempt to streamline everything into a somewhat coherent narrative, but there is more than enough music to talk about to fill several books. I will skip around as necessary to tell a compete story and maintain some degree of intelligibility. I encourage you to seek out more authoritative chronologies if this interests you, but I’m trying to keep this piece manageable in scope (and failing miserably).

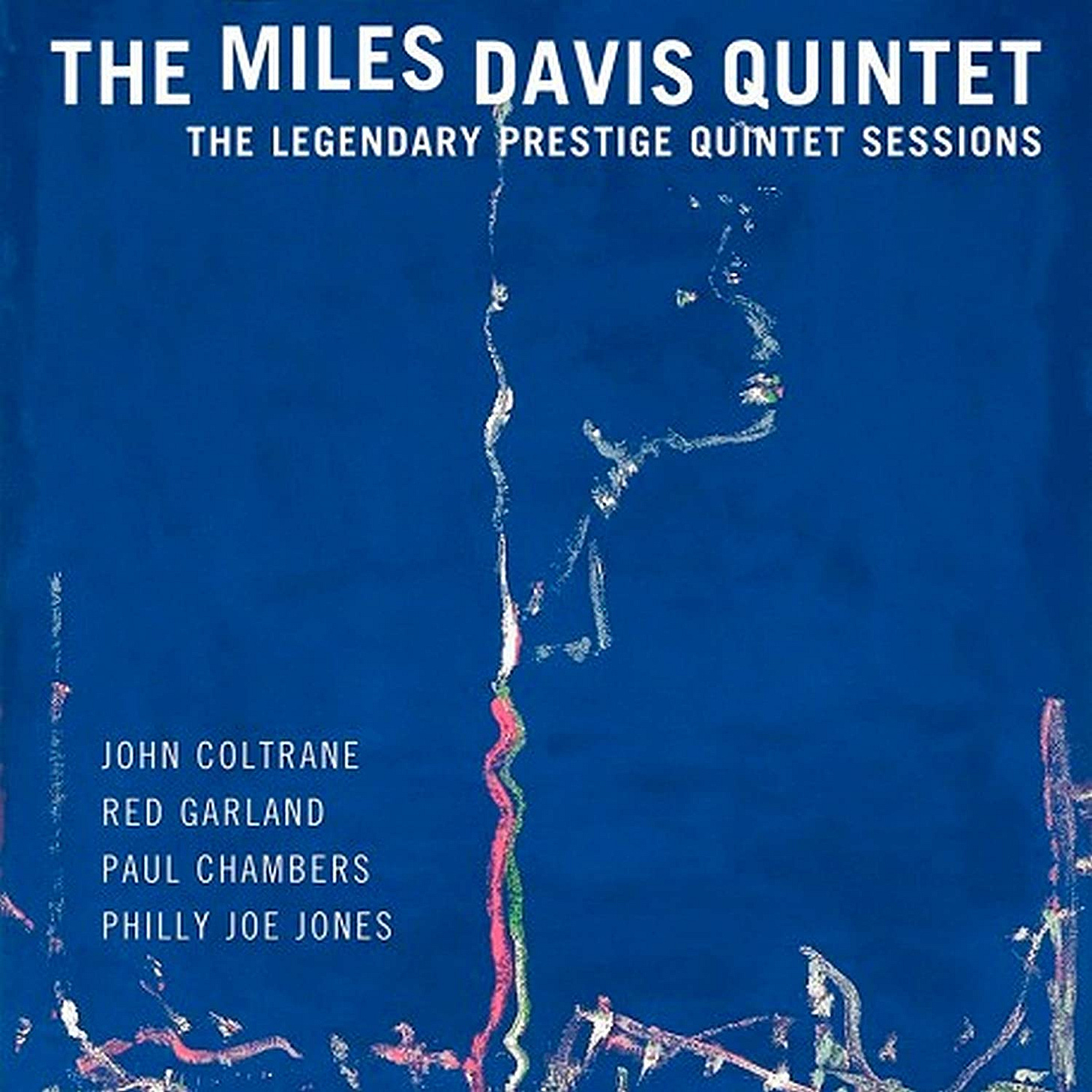

In 1955, Davis formed the first incarnation of the Miles Davis Quintet after a spotlight-stealing performance at the Newport Jazz Festival. He signed a lucrative deal with Columbia Records that would begin once his Prestige deal ran out later that year. Columbia asked Davis to assemble a group to pursue the furthest reaches of hard bop; he recruited Red Garland on piano, Paul Chambers on bass, and Philly Joe Jones on drums, alongside Rollins on saxophone. Rollins was only with the quintet for a short while before leaving to address his heroin addiction, and Jones suggested a young upstart from North Carolina as his replacement: John Coltrane.

“Trane” was the perfect counterpoint to Davis’ style; where Davis used smooth, elegant melodies as the base of his parts, Coltrane injected fire and verve into every solo. The combination was an absolute winner. Thanks to record label politics, the Quintet had to record several albums worth of material for Prestige before they could begin releasing new tracks for Columbia. The newly formed group spent three days over the course of the next year, working in marathon sessions to produce five albums: Miles, Cookin’, Relaxin’, Workin’, and Steamin’ with the Miles Davis Quintet, all of which were to be released over the next five years. If you get the chance, listen to the four disc box set The Legendary Prestige Quintet Sessions, which contains everything recorded in those three days plus some contemporaneous live performances.

The first incarnation of the Quintet lasted less than two years; substance issues from Jones and Coltrane resulted in their firing, whereupon Sonny Rollins rejoined in addition to drummer Art Taylor. That configuration didn’t last long. Once the Prestige obligations were over and Columbia was funding the band, the members were now being paid for rehearsals which allowed them to stand on firmer financial footing. Jones and Coltrane returned in 1958, and Julian “Cannonball” Adderley was added as an additional saxophone to make the Miles Davis Sextet. Their first album for Columbia (titled Milestones) captured a more mature musical approach.

Davis had worked with several different bands over the previous years in a number of settings, including scoring films with a French jazz group and continuing to explore what would become known as “third stream”, a hybrid of classical and jazz idioms. Soon, Davis would incorporate this diversity into sessions with arranger Gil Evans under the auspices of Columbia Records. Evans and Davis had collaborated at the beginning of the decade on a more orchestral setting than usual, with the results coming out in 1957 under the title Birth of the Cool. Their newer work leaned even more towards classical textures, with the three albums Miles Ahead, Porgy and Bess, and especially Sketches of Spain clearing new territory for jazz. A fourth album with producer Teo Macero titled Quiet Nights even combined the orchestral arrangements with Brazilian bossa nova, although Davis was unhappy with the results and broke ties with Macero for several years afterwards. Davis frequently swapped out his trumpet for its close cousin the flugelhorn on these classical-leaning dates, preferring its mellower sound and more flexible timbre to contrast with the expansive orchestral arrangements.

On the more mainstream jazz side, the Sextet changed lineups once more when Garland was replaced by Bill Evans on piano, and Jones departed again for the drum work of Jimmy Cobb. Bill Evans (not to be confused with Gil) bridged the gap between third stream and jazz, with a substantial background in classical music serving as his foundation. Davis pushed the group away from more straightforward arrangements based on major and minor tonality, asking the soloists to work with modal sketches instead of chord progressions. (For the record, my formal music theory is shaky. I can play along with most of this stuff, but the mechanics sometimes escape me. I blame my roots in country music.) Bill Evans was key to this approach, as he didn’t “think” like a jazzman when providing accompaniment. When Bill grew tired of touring and performances within six months, his replacement Wynton Kelly tried to mimic his skillset, although his tastes ran more towards blues than classical.

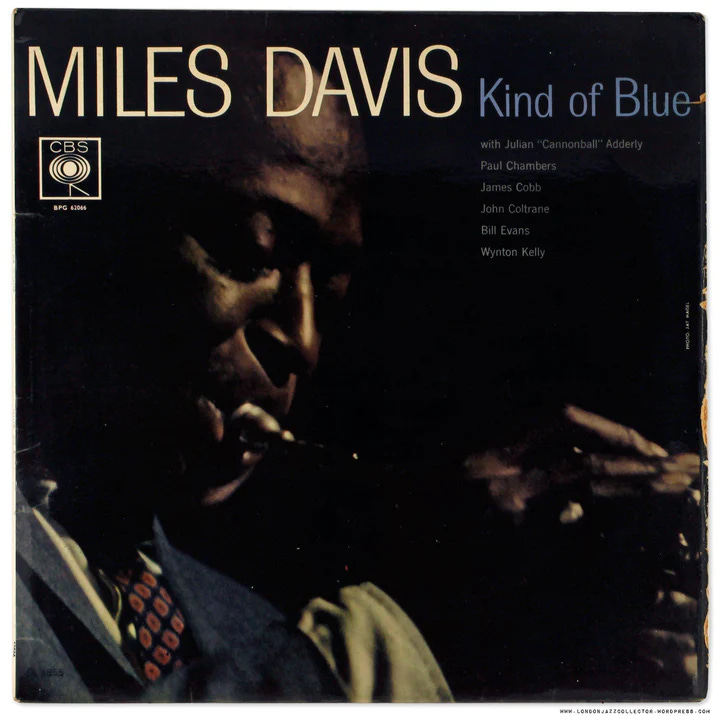

Miles Davis began working on modal jazz in earnest, even after the departure of Bill Evans. He collated five pieces that encapsulated his approach: “So What”, “Freddie Freeloader”, “Blue in Green”, “All Blues”, and “Flamenco Sketches”. Over the course of two sessions at Columbia in the spring of 1959, he recorded what may be his magnum opus, Kind of Blue. Once he settled on a track list right before recording, he asked Evans back for these limited engagements. Kelly was unhappy, especially because he was given no notice beforehand, but he played on “Freddie Freeloader” as a concession.

Kind of Blue invented modern jazz, along with its contemporaries Time Out by the Dave Brubeck Quartet and Giant Steps by our old friend John Coltrane. Giant Steps in particular explores the same modal idiom as Kind of Blue, which Coltrane would push even further on his subsequent A Love Supreme and My Favorite Things. (Someone remind me to do a full Coltrane piece later.) Time Out is rooted in Davis’ earlier bebop, but slower and with off-kilter rhythms that play with tempo and time signature in the same way that Kind of Blue plays with scales and chords. Those three albums together are the foundation of jazz to come, and make for a great introduction to jazz for newcomers; if you don’t appreciate those three, maybe jazz isn’t your thing?

In the wake of the album, the Sextet toured for the final time. Adderley left first, reverting the group into its original quintet. Coltrane was the next to leave, in order to pursue leading his own band much like Adderley. After filling in the gap with Hank Mobley, the lineup shifted tremendously over the next several years. Eventually, the Second Great Quintet would take shape by 1964: Ron Carter on bass, Herbie Hancock on piano, Wayne Shorter on saxophone, and Tony Williams on drums. Initial gigs were delayed by Davis’ health problems; he suffered a hip injury and spent months in the hospital, in addition to his ongoing reliance on alcohol and cocaine that resulted in a second months-long hospital stint.

Once Davis recovered somewhat, he resumed both performing and recording with his new group, incorporating more of the old bebop feel into the newer modal arrangements. The group took a more communalistic approach to their music, with the individuals having more freedom to determine their role in the band. As they congealed into a cohesive unit, they began to fall into predictable patterns much to their dismay. Part of their perceived mission was to explore new territory in jazz and to subvert expectations, so they set out to deliberately contravene the “rules” of jazz.

Davis was simultaneously inspired and repulsed by some his contemporaries, in particular Ornette Coleman. Coleman pushed the boundaries of modality into a new form: free jazz. Stripped of constraints in terms of rhythm, melody, accompaniment, and voicing, free jazz removed the clothing covering jazz and laid it bare. Davis thought Coleman went too far, removing structure for the sake of innovation while sacrificing the inherent musicality of jazz. Although he was dissatisfied about the end result achieved by Coleman, his new quintet used some of the same techniques to propel the genre forward. (Of course, Davis being the contrarian he was, he denied Coleman’s influence entirely.)

Their new vision for jazz came to fruition at the Plugged Nickel in Chicago on December 22nd and 23rd, 1965. On the way there, Williams sat down with Shorter, Hancock, and Carter on the plane ride to discuss their approach. Williams suggested intentionally subverting their instincts so as to create new musical opportunities; for example speeding up the tempo when they would usually slow down, or changing keys during a solo to shift the tonal center of a song. What’s more, they made the collective decision not to tell Davis of their plan.

Over the next two days and seven sets, they played almost eight hours of inventive, innovative, and intriguing music that danced at the edges of what was possible. The setlists by Davis were a combination of old standards from the Great American Songbook (such as compositions by Cole Porter, Lorenz and Hart, and Sammy Cahn) and stalwarts of Davis sets for years (including “The Theme”, “Milestones”, and “So What”), but in most cases radically reinterpreted with the vigor of a new band and a new direction. Luckily, all seven sets were recorded and are available as The Complete Live at the Plugged Nickel, released for the first time in 1995. Just as The Legendary Prestige Quintet Sessions are the definitive record of the First Great Quintet, this release is the same for the Second Great Quintet.

In 1966, Davis and the Quintet returned to the studio to record several albums worth of material, initially following the template of the Plugged Nickel performances and their newly formed sub-genre “post-bop”. Post-bop is more notable for what it’s not: it’s not bebop like Rollins, it’s not free jazz like Coleman, and it’s not West Coast jazz like Dave Brubeck. Five albums emerged from sessions over the next two years: Miles Smiles, Sorcerer, Nefertiti, Miles in the Sky, and Filles de Kilimanjaro.

Each album pushes the boundaries of the poorly defined genre, with a pivot occurring around Miles in the Sky. At those sessions, Hancock and Carter began using electric instruments (Fender Rhodes piano and electric bass respectively), while the second track “Paraphernalia” features future smooth jazz legend George Benson on electric guitar. The public outcry from jazz fans was not of the same intensity as that faced by Bob Dylan when he went electric at 1965’s Newport Folk Festival, but the sentiment was similar.

When Coltrane died in 1967, critics remarked that jazz as it was known was “dead”. Whether that passing directly impacted Davis’ musical direction is unclear, perhaps even to Davis, but the loss did change his perspective on his life. Already, Davis had moved out of traditional jazz venues for most concerts, preferring to play larger college theaters and places that skewed to a younger and more diverse audience. He began listening to more popular music, in particular other artists with R&B roots like Sly and the Family Stone, David Axelrod, Jimi Hendrix, and James Brown.

I imagine three out of those four are familiar to the majority of my readers. Axelrod was a jazz and soul producer for Capitol Records in Los Angeles who made the transition to solo works. He was one of the first to combine “rock” instrumentation like electric guitar, electric bass, and synthesized organ with jazz idioms on his first two albums Songs of Innocence and Songs of Experience. (Yes, my fellow English majors, they are both based around the works of William Blake.) In one of the contemporary reviews for Songs of Innocence, a critic remarked that the music was akin to a “jazz fusion”, coining the name for the mix of rock and jazz that was to come.

Davis was an avid listener of Axelrod, and took direct inspiration from his Blake albums to create a new sound. On Filles de Kilimanjaro, Hancock gave way on piano to a new talent named Armando “Chick” Corea, while Carter moved on to make room for bassist Dave Holland. The rejuvenated rhythm section was completely reworked when Williams left at the conclusion of those sessions. Jack DeJohnette was hired as his replacement, although Williams and Hancock were on good enough terms with Davis to be recalled for session work if necessary. Two new musicians were brought in as additions for sessions rather than replacements. Joe Zawinul joined to add electric piano and organ textures, while Englishman John McLaughlin was the first electric guitarist to join Davis’ retinue.

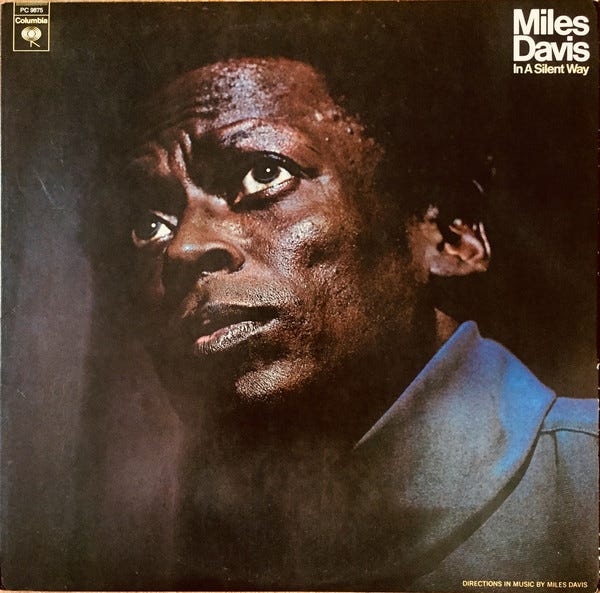

On February 18, 1969, the new band plus Hancock and Williams (though minus DeJohnette) convened with Teo Macero (with whom Davis had reconciled) to produce In a Silent Way. The musicians played for three hours, working their way through four separate songs: “Shhh”, “Peaceful”, “In a Silent Way”, and “It’s About That Time”. Davis was the composer for three out of the four, with the title track originating with Zawinul. Rather than run through each song multiple times and trying to get the best combined performance each iteration, Macero used techniques from popular music by taking individual sections and splicing them together to create a definitive take. The four songs were grouped together in pairs, following an A-B-A format on each side of the LP. The music itself was intentionally devised to bridge the gap between jazz and rock, becoming one of the cornerstones of the nascent jazz fusion genre.

Critics were divided by genre in their response. Rock critics like Lester Bangs of Rolling Stone thought the album was inspired genius, achieving new heights in musical ingenuity. Jazz critics thought that In a Silent Way marked the final death knell of “Jazz as We Know It”, and gave mixed reviews. Audiences from both sides of the jazz/rock divide were enthused, though, with the album charting at number one thirty four (making it Davis’ first album to chart in five years). The group toured behind the album, with DeJohnette taking his place behind the drum kit. Unfortunately, the combination of Davis, Corea, Holland, Shorter, and DeJohnette (referred to as the “Great Lost Quintet”) never made a complete studio recording although their European performances are widely available through bootlegs.

This brings us back to the top of our article. For the next session in August, Macero hired several new musicians for Davis to work with. In addition to the Great Lost Quintet, DeJohnette, McLaughlin, and Zawinul, there were six more musicians invited to participate: Bennie Maupin (bass clarinet), Larry Young (piano), Harvey Brooks (electric bass), Lenny White (drums), Don Alias (percussion and drums) and Juma Santos (percussion).

Rather than provide detailed notes, Davis (in conjunction with Shorter and Zawinul who each wrote one song) gave the musicians mere suggestions and let the experts follow their instincts. The band was provided with chords and moods, with vague intimations of melodies. After a week of rehearsals, they converged on Columbia’s 52nd Street Studios in Manhattan. Each of the three days of recording went the same: assemble by 10:00AM in a half circle with Davis and Shorter in the middle, all wearing headphones and focusing entirely on the music for three solid hours. Davis’ goal was to maintain an air of improvisation, capturing the creative energy that comes with rapid-fire inventiveness. As such, no guests were permitted in the sessions; only Macero and the engineers Frank Laico and Stan Tonkel attended, though legendary drummer Max Roach snuck in to observe at least some of the recording.

Once the sessions were complete, the group went to Davis’ apartment where they played through the tapes to decide what to keep. The musicians were surprised by how much the songs had changed from their initial conception as sketches. Davis and Tecero then spent the next six months crafting the finished product, using effects and loops to build a definitive take for each song. Tecero was given free reign to rearrange the basic forms of the music, altering the order and moving sections around to fit the desired vibes. Some songs had individual notes repeated by copying and splicing tape, while others were run through custom-built effects units to provide new and innovative textures to the parts. Tecero’s role in the finished album is as much sculptor as it is producer, adding and subtracting to create a unified vision. Davis being Davis, Tecero was not praised at the time for his contributions, with Davis rarely mentioning him positively in interviews or even conversation.

Let’s now move track by track through the album, starting with the opening number.

A1. Pharaoh's Dance

The opening track (taking up an entire side of the first LP) features Young on piano, with his part mixed in the center while Zawinul and Corea are panned to each side. White and DeJohnette provide the drum parts with Alias and Santos supplementing the additional percussion. “Pharaoh’s Dance” is perhaps the most manipulated track on the album; when it was remastered in the late Nineties from the original tapes, producer Bob Welder and master engineer Mark Wilder counted dozens of edits. As a result of the extensive edits, Davis never performed the song in concert in whole. In many regards, the studio itself is an instrument as much as Davis’ trumpet. Davis’ parts throughout the album are front and center, mixed more like a singer than an instrument, leaving no doubt that he is the star of the performance. Zawinul was not pleased with how Davis took over the song, and was even less impressed when Davis attempted to usurp co-writing credit from his composition just before the recordings began.

B1. Bitches Brew

The title track takes up the second side of the album, and is the longest piece in the suite at twenty-seven minutes of runtime. The lineup is the same as “Pharaoh’s Dance” with the omission of Young. This song was actually the first song recorded in the three day session. Initially, the first two sections of the song were switched, with the bass solo originally serving as the introduction. Macero and Davis swapped things around in multiple variations before settling out on this order. They then took what was going to be the third and fourth sections and singled them out into their own track on the next side.

C1. Spanish Key

“Spanish Key” has the same lineup as “Pharaoh’s Dance”, complete with Young taking the central piano line. Davis’ original intent for the album as a whole was based on three separate keyboard voices, but it is only on those two tracks that the idea comes to fruition. The skeleton of the song had been worked out by the quintet when they were out on the road supporting In a Silent Way, however this version takes liberties with that outline. The tonal center shifts modally, moving from D to E to G instead of staying in one key like the majority of the other songs here.

C2. John McLaughlin

Named after the guitarist, this song is unique on the album as it doesn’t feature Davis or Shorter at all. Instead, Davis served as conductor of his miniature orchestra. In fact, you can hear him whisper instructions to several musicians throughout, much to the chagrin of Macero. This song was derived from the intended middle sections of “Bitches Brew”; the first two survived, while the last section was discarded entirely. Both Davis and Shorter recorded solos based on this theme, however there were technical issues with their headphones so they were unsatisfied with their performances.

D1. Miles Runs the Voodoo Down

Inspired directly by Jimi Hendrix’s “Voodoo Chile”, Davis spent the entire second day of recording working on this track after refining it in the previous year’s live performances. At first things went well, but soon the drum work grew irritating to Davis. Both White and DeJohnette were attempting to “fill the space” with intricate polyrhythms instead of letting the song breathe. Davis’s mood soured more and more until Alias stepped in with a suggestion. He took White’s place behind the left drum kit and began to play a looser, freer part inspired by hearing second-line bands in New Orleans that year during Mardi Gras. Davis leapt upon the idea, kicking White out of the session and imploring DeJohnette to follow Alias’ lead. After a substantial amount of time and a good amount of cursing towards DeJohnette (audible on the expanded edition of the recordings), the band settled into a solid groove with a particularly nice solo from McLaughlin.

D2. Sanctuary

Shorter had composed this piece almost two years earlier, and the band had worked out many of its intricacies on tour. Davis, as was his custom, attempted to obtain co-writer credits for the melody but Shorter refused. This song features the fewest performers on a track, with McLaughlin, Maupin, Brooks, and White all sitting out. The notable impact from Macero’s production was the repetition of entire sections in the piece, including a doubled false ending. The way the song never resolves into a solid chord progression is indicative of the overall direction of the album; by refusing to follow traditional jazz conventions, Davis’ arrangement reflects the growth of his music into unexplored territory. It’s a fitting end to the album.

Bonus. Feio

A bonus track on the 1999 reissue of Bitches Brew, “Feio” was not recorded in the original three days of studio time like the rest of the album. Instead, it came from a session in early 1970 that featured three lineup changes. Brooks was absent, leaving Holland to play electric bass alone. White had also left, to be replaced by the relatively untested Billy Cobham on drums. Finally, Jumo Santos and Don Alias were replaced by Airto Moreira, who in the intervening months had become a big influence on Davis’ sound with his own Latin flavor. “Feio” was essentially a reworking by Shorter of a Crosby, Stills, and Nash song titled “Guinnevere” from their first album that came out in May 1969. David Crosby believed it to be one of his finest moments as a songwriter, though it did not have the same success as Stephen Stills’ “Suite: Judy Blue Eyes” or “Helplessly Hoping”.

After the release of Bitches Brew on March 30, 1970, both critics and audiences were resolute in their excitement. The album would ultimately sell more than a million copies, proving to be Davis’ second most successful album in his career behind Kind of Blue. It was number one on the Jazz Albums chart, and reached number thirty five on the overall Billboard Hot 200 charts spanning all genres. Critics responded with near universal acclaim. Only scattered malcontents like Steely Dan’s Donald Fagen decried the album entirely. That isn’t to say that the album is flawless. Indeed, most listeners saw it for what it was: a bold statement that took risks and covered new ground, landing most of its punches but not all.

In the aftermath of the album’s production, nearly all of the band would leave to pursue other projects. Some, like Shorter and Zawinul left on less than stellar terms; Davis’ approach to songwriting credits played a large role in their estrangement. Others returned on occasion like Hancock had earlier. The crew from Bitches Brew would go on to form many other fusion groups in the wake of Davis:

Zawinul and Shorter would combine with bassist Miroslav Vitouš, percussionist Barbara Burton, and drummer Alphonse Mouzon to form Weather Report, frequently augmented in their early years with Airto Moreira and Don Alias on percussion. Later lineups would include such stalwarts as Jaco Pastorius (arguably the greatest jazz bassist of all time) and drummer Omar Hakim.

Corea and Moreira joined with bassist Stanley Clarke, saxophonist Joe Farrell, and Moreira’s wife Flora Purim on vocals to form Return to Forever. Later, both Steve Gadd and Davis veteran Lenny White would join behind the drum kit, while guitarists Bill Connors, Earl Klugh, and Al di Meola would cycle through.

McLaughlin would pursue a solo career at first, frequently with Larry Young as an accompanist. His solo excursions would grow into the Mahavishnu Orchestra, supported by bassist Rick Laird, keyboardist Jan Hammer (of later Miami Vice fame), violinist Jerry Goodman, and Davis veteran Billy Cobham. Over the years, the lineup changed to include Narada Michael Walden on drums and Jean-Luc Ponty on violin.

Hancock also pursued his own bands, at first with his group Mwandishi featuring Bennie Maupin, then later with his Headhunters (also with Maupin). Eventually Hancock pushed into more funk territory, culminating in his surprise hit “Rockit” in 1983.

Davis went on to record Jack Johnson for a 1971 release, followed by Live-Evil later that year and On the Corner the next. No two lineups would remain the same; Davis’ reputation as hard to get along with increased during this period, and his musical vision was impacted by his desire to chase after financial success. Whereas Jack Johnson and Live-Evil sold a substantial number of albums (though diminished from the heights of Bitches Brew), On the Corner in particular is a nakedly commercial release. It’s also spectacularly unsuccessful from both an artistic standpoint and a financial one; it was immediately panned on release as soulless and uninspired. More than one critic called it an insult to listeners.

After this failure Davis stopped working on discrete albums of material, instead focusing on scattered sessions that would be assembled into compilations. Big Fun and Get Up With It were devised under this scheme, both to resounding silence from the record buying public. Live albums like Agharta, Dark Magus, and Pangaea were occasionally released during this time period with mixed results.

Finally, Davis dropped out of music completely after 1975, right after negotiating his new contract with Columbia. His growing drug problems contributed greatly to this decision; he relied on cocaine, alcohol, and opiates to get through shows thanks to his mounting physical ailments. His dissatisfaction with the music industry was at an all time high as well, while his finances were at an all time low. Despite the advances from Columbia, he was burning through money faster than it was coming in. His nadir was in 1978 when his son Erin’s mother had him jailed for failure to pay child support.

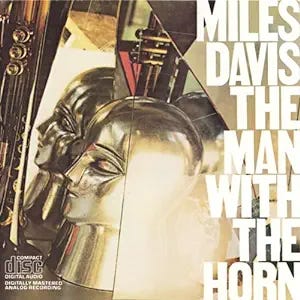

In 1980, Davis returned to music with The Man with the Horn, again produced by Macero. Despite poor reviews, the greater listening public was curious enough to buy a sufficient quantity to rebuild his career. He toured behind it, though his issues with alcohol came to a head in January of 1982 when he suffered a stroke in Africa. He was nursed back to health by his then-partner, actress and activist Cicely Tyson, who suggested a regimen of exercise and art therapy in conjunction with his medical team.

1983’s Star People was a return to form, becoming the best reviewed album of this era of Davis’ career. 1984’s Decoy was less successful artistically, as he attempted to mimic the approach of Hancock’s “Rockit” with no real soul. Tensions were so fraught with his label that Columbia delayed releasing the album in the hopes that he would rework it. His last album for Columbia would be 1985’s You’re Under Arrest, featuring two covers of popular songs: Cyndi Lauper’s “Time After Time” and Michael Jackson’s “Human Nature”. The album was a flat end to a relationship that lasted for almost thirty years.

Davis’ last years were marked by a decline in health, culminating in rumors of autoimmune disease. He only released two albums for Warner Bros. in his lifetime, neither of which were successes. He died on September 28, 1991 as a result of a stroke combined with respiratory failure. Both Columbia and Warner Bros. released multiple editions of posthumous work, including the nearly complete Doo-Bop in collaboration with hip-hop producer Easy Mo Bee.

Miles Davis’ status as one of the giants of jazz is unquestioned. Similarly, his status as one of the most abrasive, egotistical, and outright disliked human beings in modern history is similarly gigantic. Few artists ever reach the lofty heights of Kind of Blue or In a Silent Way, but few artists are ever given the leeway to fail as concretely as On the Corner or Doo-Bop. More important to his contributions to music are his legions of sidemen who went on to resounding success; his musical family tree bears fruit to this day.

This piece would not have been possible without the work of Paul Tingen, Victor Svorinich, and Chris Baber, all of whom wrote exquisite pieces that provided much-needed context for Bitches Brew. Their works were instrumental in delivering a higher degree of information and insight than my typical articles.

Join me next time when I write something a lot shorter and less involved. See you later, space cowboys!