Let me set the scene for you. My (now blessedly ex-) girlfriend was bored on a weekend, and wanted to watch something on television, but didn’t know what she wanted to watch. I ran through our platform options (all of the free streaming services like Tubi, PlutoTV, Xumo, and the like) and all manner of genres. How about that big dumb blockbuster movie that came out last year? Nah, too dumb. How about that quirky miniseries from England? Nah, too thinky. How about that cartoon from when we were kids? Nah, too immature. This went on for at least an hour in various iterations.

Finally, exasperated, I started to run through all of the genres and subgenres of film and TV I could reel off. The only one that didn’t get an immediate sneer or a sigh was a concert movie. I quickly racked my brain to remember the best of the best. The TAMI Show? “I don’t know any of those bands.” The Last Waltz? “Too old.” Stop Making Sense? “Wait, who’s that?”

I sensed my in. “Talking Heads. Remember ‘Psycho Killer’?” “Vaguely.” “Will this do?” “…fine.” (I don’t want to say that every conversation went this way, but more than I’d prefer to remember had this cast about them, especially towards the end of the relationship. Hindsight: I was lucky to emerge unscathed beyond emotional damage.) I spent the next hour and a half trying to reconcile my growing uncomfortableness with my companion and my love for the movie itself.

And that’s the story of how one of my favorite films is now tinged with complicated feelings for me. Such is life.

If you haven’t ever seen Stop Making Sense, fix that now. These three links provided for your convenience. It’s compelling work from a band at the height of its musical stature, teetering on the edge of pretension and innovation. The visual presentation is at once a response to the artifice of televised performance like American Bandstand or Top of the Pops and also an attempt to capture the raw energy of Elvis’s ‘68 Comeback Special or Ziggy Stardust. It is a synthesis of both, yet unlike either. Just watch it.

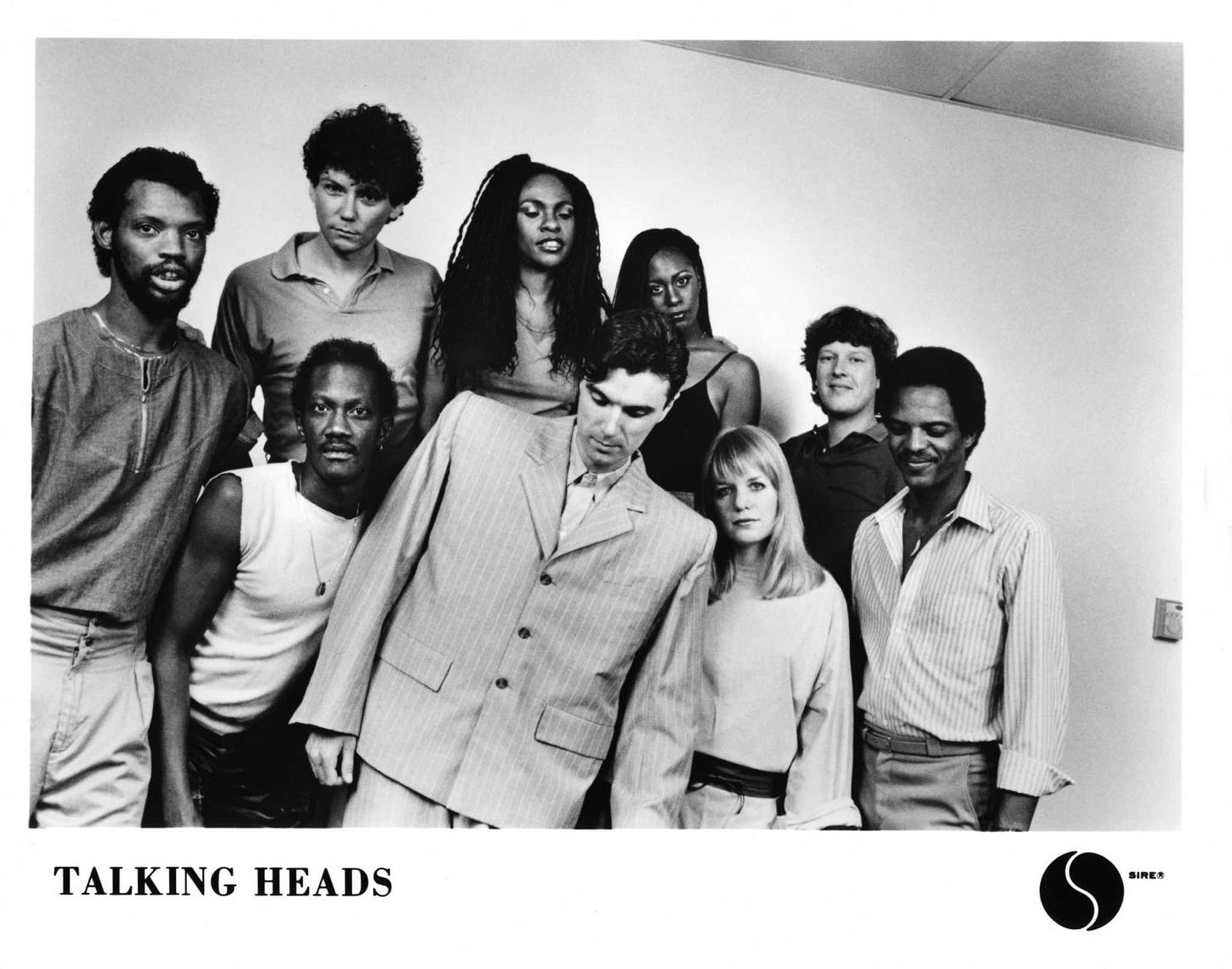

Talking Heads was formed in 1975 in New York City by David Byrne (vocals, guitar, and sometimes electronics), Tina Weymouth (bass), and Chris Frantz (drums). They had met at the Rhode Island School of Design, where Byrne and Frantz were in a band named The Artistics and Weymouth (Frantz’s girlfriend) was their frequent companion and occasional driver. When they moved to New York, the duo was unable to find a suitable bassist until Weymouth stepped in.

They began playing clubs and bars, including CBGB’s. Demos were unsuccessful at securing recording contracts at first, but their audience expanded with seemingly every show. Soon enough the industry came calling. Adding Jerry Harrison as a multi-instrumentalist helped flesh out their sound, and he had experience with Jonathan Richman’s Modern Lovers that aided their navigation of the music scene. His joining was contingent on securing a record deal, though, as he was enrolled in graduate school at Harvard after the end of the Modern Lovers and wasn’t going to leave school for on a whim. Seymour Stein with Sire had previously expressed an interest in 1975 in signing them, but the band didn’t feel comfortable with either the terms of the deal or their own abilities on stage to sign.

After working for two years and talking it over with Lou Reed and the Ramones’ manager, the band reconsidered and signed with Sire. In 1977, they released their first single, “Love → Building on Fire”, produced by Tony Bongiovi (Jon’s cousin!) and Tommy Ramone. Talking Heads: 77 was their first album, released in September of that year. “Psycho Killer” was a moderate hit, especially for a young unproven band. The recording process was unpleasant for the members, especially Byrne who was unsettled with Bongiovi’s strange behavior (including asking Byrne to “get in character” by singing his parts for “Psycho Killer” while holding a large knife).

More Songs About Buildings and Food in 1978 was a much better experience, as they utilized the services of friend Brian Eno for production. They focused the presentation on the deeply grooved rhythm section, and were much better for it. Weymouth’s relative lack of training when playing bass meant that she didn’t have any bad habits to unlearn, and felt none of the constraints of regimented instruction. Frantz’s snappy, agile acoustic drums were the perfect counterpoint, and the quantized rhythms melded well with Byrne’s programmed drums. “Take Me to the River” was a cover of an Al Green song that was an unlikely minor hit, reaching #26 on the charts.

Fear of Music in 1979 built upon the momentum the band had generated, moving them into the direction of art music rather than mainstream music. Strangely enough, the more they moved away from popular music the more they imitated the rhythms of disco, specifically with the use of Frantz’s hi-hat work. In particular, “Life During Wartime” with its dance-punk angularity is a revelation. Brian Eno produced the album, recording the basic tracks in Frantz and Weymouth’s apartment by running cables from the mobile recording studio in the parking lot into the window of their loft. Despite widespread critical acclaim, the album only hit #21 on the Billboard 200.

1980’s Remain in Light was a portrait of a band in tension. The members took a break from one another after the previous album’s tour, where Byrne recorded an experimental album with Brian Eno (My Life in the Bush of Ghosts), Harrison produced an album for Nona Hendryx (formerly of Labelle and an occasional backing vocalist for Talking Heads), and the rhythm section decamped to the Caribbean for an extended vacation. Weymouth in particular was growing frustrated with the image of Byrne as the “talent” and the rest of the members as his backing band, and floated the idea of quitting entirely to Frantz. Instead, the band revamped its creative process, shifting from a sole composer in Byrne to a more concerted group effort. The band also made a conscious move towards incorporating African and Caribbean stylings into their music, basing the whole album aesthetic on Fela Kuti’s Afrodisiac.

As a result of the expanded musical palette, the touring musicians expanded. Guitarist Adrian Belew (of King Crimson), keyboardist Bernie Worrell (of Parliament Funkadelic), bassist Cherry Jones, and percussionist Steven Scales were recruited alongside backing vocalist Dolette McDonald.

The tour itself was tense; at the end of the recording process, Byrne and Eno were the only credited composers for much of the album despite the contributions of the entire band. Weymouth was furious, as she had extreme trepidation about Byrne’s integrity to begin with, and this added fuel to the fire. The promotional materials focused on Byrne’s contributions to the lyrics to the exclusion of all others.

In the aftermath of the tour, Harrison recorded and released a solo album, Byrne continued working with Eno, while Frantz and Weymouth formed Tom Tom Club. Of these, Tom Tom Club has proven the most successful and has the largest lasting impact. “Genius of Love” is amongst the most recognizable samples in the history of recorded music. The break lasted almost three years, although Talking Heads did tour together during the recording hiatus.

In 1983, Speaking in Tongues was released, the first album the band produced themselves after Eno exited the producer’s chair. It’s their most successful album commercially, peaking at #15 on the Billboard 200 and the origin of their highest charting single, “Burning Down the House”. The formula came together, incorporating the electronic tinge from Tom Tom Club, the experimentalism of Byrne’s solo work, and the sheer funkiness of the group as a whole. It’s from this tour that their apotheosis emerges, as Stop Making Sense (released in 1984) captures the artistic peak of their output. It’s as close to perfect as one could reasonably expect any band to produce. This would also be the last tour for Talking Heads.

Little Creatures came out in 1985, and represents Byrne’s increasing control of the band’s output. His leanings towards outsider music and esoteric country influence emerged. 1986 saw the release of True Stories, an album designed to serve as the soundtrack to Byrne’s film project of the same name. Of note is the second track on side two that inspired the name of Radiohead.

The final Talking Heads album Naked was released in 1988. In retrospect, it’s a weak and unfocused product, with egos running roughshod over the proceedings. The band did relatively little to promote it, and Byrne focused entirely on his solo work beginning afterwards.

In 1991, Byrne gave an interview where he said the band had broken up. As far as the others were concerned, Byrne left rather than the group disintegrating. The three remaining members toured together under the name The Heads and attempted to release an album, No Talking, Just Head. Byrne sued over the use of the name, and the parties settled out of court prior to the album’s release in 1996. The album is not good, and the question of whether to include tracks from it in the ranking to follow is obviated by that lack of quality.

Speaking of rankings, let’s get down to it. As per usual, this represents my opinion and my opinion alone. If you don’t like it, yell at me on Twitter, in the comments below, or even better get your own newsletter right here at Substack. I am only including tracks from releases credited to all four members, but know that “Genius of Love” would definitely displace one of the tracks below were it eligible, and “Wordy Rappinghood” is a solid maybe. With that, here’s number ten:

10. Wild Wild Life

One of the highlights of True Stories, “Wild Wild Life” is more spacious and organic than much of the later period Heads material. Weymouth’s pulsing bass combines with Harrison’s angular guitar to meld into a new wave pop song. With one foot in funk rock and another in art pop, it’s the story of Talking Heads: both funkier and artsier than their CBGB peers. If you watch the video, keep an eye out for John Goodman in an early appearance.

9. Road to Nowhere

Jerry Harrison’s organ part carries the day here, but the whole orchestration works together, including Frantz’s martial drumming and accordion work from Jimmy Macdonell. The song is built around a simple vamp, with just two chords. There’s a distinct gospel tinge to the proceedings, which is seemingly out of place unless considered in the context of African rhythms. Byrne’s vision of a visual aspect to the music comes to the forefront with Stephen R. Johnson’s video tricks, ones he would use to great effect in Peter Gabriel’s “Big Time” and “Sledgehammer” videos the next year.

8. Once in a Lifetime

'“Once in a Lifetime” is one of the most atypical basslines in the Talking Heads catalogue, which covers a substantial amount of ground. Co-composer and producer Brian Eno was insistent that the first note was extraneous, as he believed the rhythm to be shifted half a measure back. Weymouth disagreed, and after Eno deleted the bassline during his initial production, she and the engineer re-recorded it. As Eno’s tenure as producer continued, disagreements like this became more and more common, leading to the end of their working relationship. That this was the last album to feature his input isn’t a coincidence.

7. Life During Wartime

Let me preface this by saying there are no bad Tina Weymouth basslines, but this might be my favorite. It’s funky and punky in the best tradition of Rick James, but pointed in a different direction entirely. Something like this bassline would fit just as well in a track by Television as it would the Brothers Johnson. The addition of the congas by Ari and Gene Wilder is inspired, and presages the worldbeat flavor that would become a cornerstone of the Talking Heads sound.

6. Burning Down The House

The original version of this song is Talking Heads at their most artificial and synthetic, so it is my joy to share with you the Stop Making Sense version here:

Despite using the same instrumentation, the live performance breathes and slinks in a way that the album version doesn’t. Alex Weir’s guitar stretches and scratches against Bernie Worrell’s synthesizers in a way that suggests a twenty minute jam could break out if David Byrne would just let loose of the reins. The struggle of Byrne to maintain control, though a frequent narrative both on and offstage, creates a level of dynamic tension that permeates their entire oeuvre.

5. This Must Be The Place (Naïve Melody)

The subtitle “naïve melody” is supposedly a reference to the naivete demonstrated in its composition: the band members switched instruments to break from previous patterns, resulting in Weymouth on guitar and Harrison on (synth) bass. The lead synthesizer parts were generated without looking at manuals or previous technique, so the glissandos and sweeps aren’t smooth and effortless like they “should” be. The result is sparse and blank in comparison to the usual lushness and fullness from the synthesized lead.

4. Psycho Killer

In lesser hands, the driving bassline of “Psycho Killer” would become a bludgeon of a blunt instrument, but in Weymouth’s capable hands, it breathes and pivots with a lightness and tactile sensuousness that scintillates. It propels the song forward with a dire insistence, but never stifles or surrounds. The guitar stabs (pun fully intended) add tension and dimension without strangulation. (Can you talk about this song without violent imagery? Maybe you can.) Bonus link: yet another sample of a Weymouth bassline resulted in this song:

3. [Nothing But] Flowers

The beautifully jangly guitar on “[Nothing But] Flowers” doesn’t sound like the work of Byrne or Harrison, and for good reason. The good portion of the Smiths, better known as Johnny Marr, contributed guitar parts for the second single from Naked. The layers upon layers of delay and echo spiral in on themselves to create a soundscape that draws you in with a Charybdis-like whirlpool. The delicate percussion provides a base from which Marr’s lines spring forth. For a decidedly more acoustic take on the song, take a peek at Chris Thile’s version:

2. Take Me To The River

Normally I don’t include covers, but this is a necessary exception. What Talking Heads did to Al Green’s song is nothing short of incendiary, in the best way. Byrne was initially reluctant to record it, believing that cover songs didn’t fit in with his vision for the band. He was outvoted, so the band took a soulful swampy song and both stripped it down to the bare essentials and amplified its natural funkiness to the nth degree. The organ pops and crackles, the bassline thuds and booms, the drums echo and snap. Whether Talking Heads appropriated or appreciated black music is a matter of personal interpretation, but whatever they did they did excellently here.

1. And She Was

In direct contrast to the stark nakedness of “Take Me to the River”, there’s more going on in “And She Was” than in perhaps any other Talking Heads song. Every second is full to the brim with sound and excitement. From the tremolo laden guitar to the synth stabs to the ping-pong organ, it’s dense and layered like a pound cake. Each texture and sensation envelops the listener like a caftan. I know that other people prefer other songs, but if I were to introduce someone to what Talking Heads sounds like in total, this is the song I’d use.