In August 1968, England was a happening place for musicians, even outside of the musical centers of London and Liverpool. A lively and ever-changing music scene meant that bands could break up, reform, and mutate into new groups in the span of days and weeks. Two of those bands were Mythology and Rare Breed.

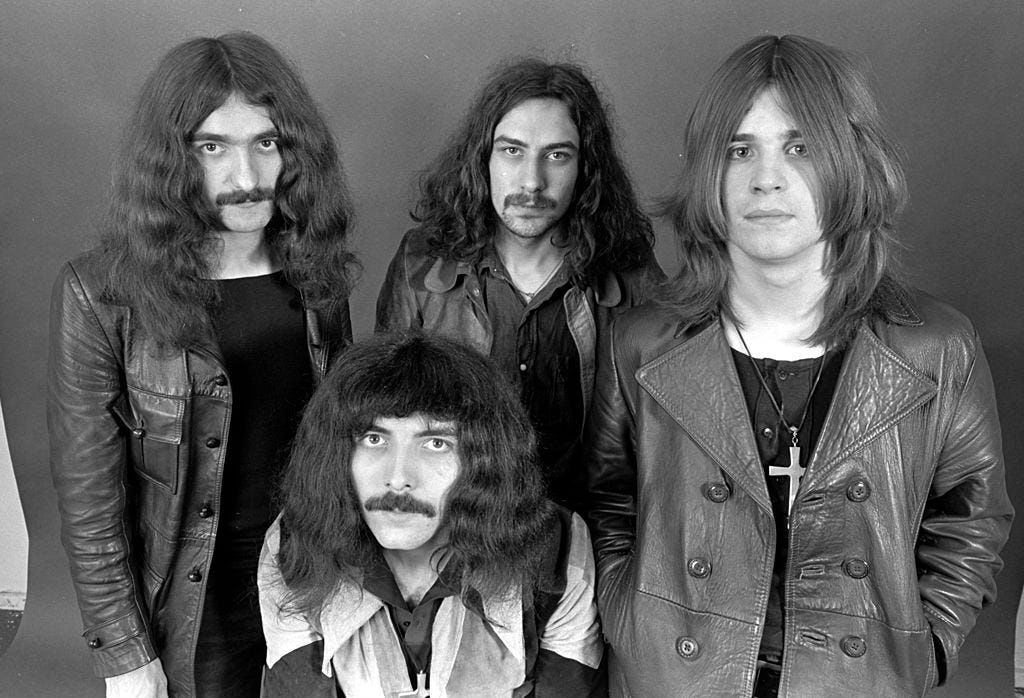

Mythology, based in Carlisle, was formed from the remnants of two other bands, the Rest and the Square Chex. At the time of its breakup, Mythology consisted of singer Chris Smith, bassist Neil Marshall, guitarist Tony Iommi, and drummer Bill Ward. (Don’t get ahead of me, you bright young readers who recognize a couple of those names.) By May of 1968, they had created a local reputation as rock and roll musicians, but it all came crashing down when all four members of the band were arrested for possession of cannabis resin. Upon their release they had a hard time booking gigs, so by July of that year they were no more. Iommi and Ward, both natives of Birmingham, returned home.

Rare Breed was a five piece band formed in Aston, with guitarists Roger Hope and Terence Butler, bassist Mick Hill, drummer Tony Markham, and vocalist John Osbourne. (Again, quiet down.) Their music leaned into psychedelia as opposed to the blues of Mythology, with costumes and face paint frequently featured. The band lasted only a handful of shows before collapsing in a fit of apathy and incompetence. Of note, only Osbourne and Butler were willing to quit their day jobs to pursue music full-time.

When Iommi and Ward returned to Birmingham, they began making plans to start a new band as soon as possible. The duo reached out to one of the musicians they knew in the neighborhood, one Terence Butler (affectionately called “Geezer” by his friends). Having already conscripted saxophonist Alan Clarke and guitarist Jim Philips, there was no room for another guitarist so Butler was convinced to switch to bass. The only missing piece was a singer. Butler recommended his former Rare Breed bandmate, John “Ozzy” Osbourne. At first, Iommi was hesitant as he and Osbourne had attended the same school and had not gotten along, but was convinced by his need to perform and Butler’s vouching.

Together, the six of them formed the Polka Tulk Blues Band, a name that would become legendary in music history. Well, maybe not. Iommi quickly learned that there was no room for that many instruments when he began playing in a heavy, dense style. Clarke and Philips soon departed, and the band changed its name once more to Earth.

Iommi’s sound arose when he was injured in an industrial accident at a sheet metal plant, causing him to lose the fingertips on his index and middle fingers on his right hand. After despairing about his prospects as a guitarist, his former foreman introduced him to the music of Django Reinhardt. Reinhardt had suffered burns on his hands, and used only two fingers to fret his guitar. Despite that, Reinhardt was as proficient as anyone in playing his brand of Bohemian jazz. Inspired by that example, Iommi continued to play with two handmade prostheses and some modifications to his technique, such as using less complicated chords and emphasizing rhythm.

Before they could really get off the ground, Iommi was offered an opportunity that he couldn’t pass up. Jethro Tull was looking for a new guitarist, and Iommi was selected. With the rest of the band’s blessing, he took the gig. Unfortunately, he didn’t enjoy any aspect of it, butting heads with Tull’s management and not gelling musically. After only a few weeks, Iommi was back in Birmingham with Earth.

Upon his return, Earth started booking bigger gigs with more publicity. The most notable performance of this era was opening for Ten Years After, which attracted the attention of Jim Simpson, a local music manager. He signed them and quickly sent them on the road to Hamburg, Germany. The Beatles made their name in the Star Club there, and Earth were determined to do the same. Playing multiple sets night after night made them a more cohesive and more professional group.

When they came back to England, it became apparent that they needed a new name. Another band of the same name had started to gain some momentum, and the confusion between the two groups was leading to frustration with promotors and fans. Butler spotted a movie advertisement for a Boris Karloff horror film, and the band agreed that it fit their dark and macabre image. Black Sabbath was born.

Simpson was able to book a recording session for the newly renamed group, as Black Sabbath had really come into their own thanks to the German performances. Typically, the band would jam with Iommi and Butler building melodies and riffs, while Ward added drum fills and Osbourne wailed wordlessly on top of it. Once the song came together musically, Butler would add lyrics using Osbourne’s vocal melodies as a guide; the rest of the band saw Butler as the most well-read and verbally adroit member and were happy to delegate the responsibility. On that first session, though, the primary output was a cover of Minnesota-based band called Crow entitled “Evil Woman”. Listen here:

It was released on the Fontana label as a one-off single, and led to a further opportunity to record an entire album. The whole process took less than twelve hours from start to finish, and each member was paid a thousand pounds by Simpson as salary. Vertigo Records, a subsidiary of Phonogram Records, agreed to release it instead of Fontana, and house producer Rodger Bain was enlisted to mix it and prepare it for distribution.

Black Sabbath was hated by critics, but surprisingly did very well with the public when it was released in February 1970. It hit number eight on the UK album chart, and a respectable twenty-third place in the US, where it remained on the charts for over a year. The album sold over a million copies, and established Black Sabbath as a force in the nascent genre of heavy metal.

By June, Black Sabbath was already in the studio again to build on the momentum they had garnered. The band employed the same compositional technique as before, jamming onstage until they found a riff or chord progression they liked and refining it into something more substantial in subsequent jams. After three days in the studio, they had put together Paranoid. Released in October of 1970 in the UK, it went to number one on the album charts quite quickly. The US distributor Warner Bros. Records wanted to delay its release there until Black Sabbath began winding down in sales. It took until January of 1971 for the record to come out there, but it sold four million copies and generated enough sales to support a US tour that year. At this point, Sabbath was one of the biggest bands in the world.

Around this time, the band fired Jim Simpson as their manager, and instead enlisted Patrick Meehan to handle their affairs. Only twenty-two years old at the time, he worked with his father to create Worldwide Artiste Management. Meehan Sr. had worked alongside Don Arden to manage the Small Faces, who were incredibly successful for a brief period in the late Sixties. (You’ll probably want to remember that Arden fellow’s name for later.)

Refusing to rest on their laurels, Black Sabbath started work on a follow-up in February, completing recording in April of 1971. Master of Reality was a critical flop when it came out in July of that year, with Robert Christgau (my mortal enemy) and Lester Bangs both panning it derisively in reviews. Just on the strength of pre-orders, the album had gone gold (selling 500,000 copies) before it was even released. During the production of Master of Reality, the band was first able to use its greatly expanded budget on one particular expense: cocaine. Each of them took to it with a fervor that would have repercussions soon enough. Musically it’s a darker and gloomier album, in part because of a tuning change and partly because of the rampant drug use. It also represented the band’s exhaustion at being on the road or in the studio nonstop for the past several years without a break. Once the tours finished, Black Sabbath took a hiatus to recuperate.

Returning to the studio in May of 1972, the band had changed significantly. Iommi took a more decisive role in the musical attitude of the band, taking the reins of production from Rodger Bain. Although Patrick Meehan was credited as a co-producer, it was largely a way to funnel money from the production budget directly to WAM’s coffers. Money flowed freely this go-round, leading to literal hundreds of thousands of dollars of cocaine making its way to the Record Plant studios in Los Angeles. Not only was it available in insane amounts, it was incredibly pure and powerful. This was on top of the prevalence of alcohol and hashish that Black Sabbath had consumed regularly over the past three albums. The psychological effects of all these substances made themselves known; the band members became paranoid that they were going to be busted, and lack of sleep led to increasingly unhinged behavior. Pranks and shenanigans kept escalating to the point that some of them began carrying weapons everywhere they went lest they become the target of a violent “joke”. In particular, Ward’s performances behind the drum kit suffered to the point where he believed he would be fired by the others.

Vol. 4 was released in September of 1972. Again, critics were unkind, and again audiences loved it. It sold another million copies, and allowed the band to tour both the US and in Europe. For the first time, Black Sabbath played in Australia to appreciative crowds. The worldwide tour lasted until the middle of 1973, when the group reconvened in Los Angeles to begin work on what would become Sabbath Bloody Sabbath. Unfortunately, Iommi was creatively spent and had a terrible case of writer’s block that lasted for months. Desperate to make something work, Black Sabbath changed venues and decamped to Clearwell Castle in Gloucestershire, England in an attempt to spur some ideas. Eventually, with the help of the dark and oppressive atmosphere of the literal dungeons underneath the castle, an album emerged.

Sabbath Bloody Sabbath came out in November of 1973, and marked a turning point for the band. After briefly experimenting with keyboards and synthesizers on Vol. 4, they became focal points for both composition and performance. (Exemplifying this approach and the emphasis on substances, Rick Wakeman of Yes guested on “Sabbra Caddabra”, refusing payment in cash and insisting on being paid in beer.) Critics had finally come around on the band, claiming that this was their best album yet. It went platinum once more, and Black Sabbath was incredibly lucrative.

Or at least they should have been. After finally settling years of lawsuits with Jim Simpson, the group decided to switch from Meehan to Don Arden’s management company. Arden was known for being “assertive” in negotiations, frequently employing his associates in the British underworld to reinforce his assertiveness with violence as he saw fit. A chunk of money was siphoned off to Arden, his son David Levy, and his daughter Sharon Arden. (Another name to remember, too.) At this point, the band was paying lawyers coming and going.

Following another year-long worldwide tour, Black Sabbath began recording Sabotage in February of 1975, releasing it in July of that year. The tension that came with all of the legal wrangling permeated the band’s compositions, with “The Writ” and “Megalomania” both calling out Meehan and his lawyers for interfering with their financial dealings. The album was their first not to sell a million copies in the US, which wasn’t helped by having to cut their national tour with Kiss short after Osbourne injured himself in a motorcycle accident. Critics were in love with it, though, proclaiming it their best album since Paranoid. (Yes, they panned Paranoid on release. Trying to find a thread of consistency in music criticism in that era is a fool’s errand.) In retrospect, though, the band was destabilizing at an alarming rate.

Things began to come to a head during the recording of Technical Ecstasy in Miami in the summer of 1976. The rest of the band left Iommi to his own devices, with Osbourne even admitted later that he was beginning to lose interest in Black Sabbath. Without the input of Butler, Ward, and Osbourne, Iommi pivoted away from the traditional metal sound of earlier albums and embraced synthesizers wholeheartedly. He invited touring keyboardist Gerald Woodroffe into the studio to help with arrangements, leaning heavily on him for accompaniment despite not sharing songwriting credits. The band began to sound more like Foreigner or Queen rather than hard edged blues rock like early Led Zeppelin. The recording process did lead to some funny moments, as the Eagles were recording Hotel California next door and frequently had to ask Sabbath to turn down their volume. (That the two bands shared drug dealers at the time is immaterial.)

Technical Ecstasy is not a good album. Let’s not kid ourselves. Neither audiences nor critics were fans, and it’s the first non-legendary album of this era of Sabbath. The tour afterwards was fraught with tension as well, as their openers AC/DC were regularly upstaging Sabbath. This led to Malcolm Young and Geezer Butler coming to blows in Switzerland one night after Butler allegedly pulled a knife on Young. (Butler says it was a comb.) By the end of the tour, everyone was sick of one another. Just as Black Sabbath was going to return to the studio for their next album in late 1977, Osbourne quit the band.

Scrambling to fill Ozzy’s shoes with the studio time already booked, Iommi reached out to Savoy Brown singer Dave Walker to step in. Walker quickly got on a plane and flew to California for rehearsals. Sabbath came up with nearly an album’s worth of material, and even performed on a BBC show in January of 1978. Listen here:

After rescheduling the studio time, Walker and the rest of the band were going to start work in Toronto in early 1978 just as Osbourne called them up with an offer. He was uncomfortable with the idea of going out on his own, and wanted to rejoin Black Sabbath. His condition, though, was that he didn’t want to perform on any material Walker helped write. Iommi had to throw out most of an album wholesale, leading to a prolonged five month stay in the studio while they wrote something new. No one in the group was in any shape to write or record, but they slogged through Never Say Die! by May.

They began touring ahead of a September release with Van Halen as their openers, although it almost ended before it started. When Van Halen took the stage, they began playing Black Sabbath songs in tribute to their heroes. Iommi believed they were making fun of them, and had to be talked down from physically confronting them. Luckily cooler heads prevailed, and the two groups got along well after that rough introduction. The tour lasted until December of 1978, with the final show in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

If Technical Ecstasy is “not good”, Never Say Die! is “beyond awful”. Reviews ranged from “disastrous” to “incoherent” to “half-hearted”. Even at the time, it was seen as a significant disappointment, barely selling 500,000 copies once all was said and done. But Black Sabbath were determined to bounce back. They spent months holed up in a mansion in Bel Air trying to write their next album.

By that point, nothing of merit had been produced. When he was coherent enough to contribute, Osbourne fought the other constantly on the direction of new material. Frequently, he was so intoxicated he was unable to speak, much less sing well. In April of 1979, things had come to a head, and Iommi made a decision. The way he saw it, he had only two options: dismantle the band entirely, or fire Osbourne so they could hire a new singer. After consulting with Butler and Ward, they made the decision to dismiss Ozzy. Ward, being the closest to him at that point, was elected to tell Ozzy he was no longer in the band. He took Sharon Arden with him as his manager, eventually marrying her. (Whether this is a good thing or a bad thing is a matter of perspective.)

And so our article draws to a close. Once Osbourne leaves the band, it’s a different animal entirely. The first eight Black Sabbath albums are a complete statement, and should be considered together. Everything that comes afterwards isn’t comparable. That’s not to say it’s bad, just that we are now in the business of evaluating apples versus oranges. For the purposes of my top ten Black Sabbath songs, I am only including material recorded by the original four members. (I may get a wild hair and continue into the later incarnations, but I’ll have to do way more research.) These are my opinions and my opinions only. I invite all manner of disagreement and dissension, so feel free to yell at me in the comments below or through all of the social media platforms you wish.

Let’s get started with number ten…

10. Supernaut

One of the best riffs in the entire Sabbath catalog, “Supernaut” closes out Side A of Vol. 4 in epic fashion. It’s one of the foundational tracks in sludge metal and desert rock, built on a monstrous guitar figure backed with Stax-style drums. The drums are an integral part of the song, with a drum solo in the middle that frequently stretched for minutes when played live. “Supernaut” also plays a significant role in the history of industrial music, as it was covered by Al Jourgenson of Ministry for his offensively named side project 1000 Homo DJs. The original cover was set to include Trent Reznor of Nine Inch Nails fame, but label politics (our old friend!) interfered. Listen to their cover to see what you think.

9. Killing Yourself to Live

The lead song on Side B of Sabbath Bloody Sabbath isn’t one of their most widely known songs, but for my money it’s one of their best. The doom and gloom riff contrasts with the tempo shifts and the synthesizer stabs, for more varied textures than perhaps you’re used to with typical Sabbath songs. It’s also the favorite Sabbath song of some notable artists, including Kirk Hammett of Metallica. Live versions showcase the booming drums and agile bassline, such as this version from the California Jam in 1974 (featuring a rare mustache-less Iommi):

8. Sabbath Bloody Sabbath

Widely acclaimed as the heaviest Sabbath song, the title track from the album of the same name represents the band at the edge of implosion. Tony Iommi famously had writer’s block for much of the lead up to this album, and it wasn’t until he came up with this riff that he believed he could continue. It’s an absolute monster of a riff, too, with a grinding and slithering rhythm that inspired countless other heavy music. It’s the favorite of Slash, who had this to say:

"The outro to 'Sabbath Bloody Sabbath' is the heaviest shit I have ever heard in my life. To this day, I haven't heard anything as heavy that has as much soul."

Listen to grindcore / noise metal mavens Today Is The Day cover the song live to get a taste of how heavy this song can get:

7. Children of the Grave

On Master of Reality, the band’s third album, Black Sabbath tuned way down one and a half steps from E standard tuning to C# tuning to make it easier for Tony Iommi to play with his injured fingertips. The results were incredibly promising, essentially inventing doom metal in one go. One of their heaviest and gloomiest songs is the antiwar anthem “Children of the Grave” that closes out Side A. It chugs and plods along with menace and majesty, creating an atmosphere as depressing and oppressive as the lyrics merit. It’s a favorite of many metal bands, but White Zombie had the most success with their cover from Nativity in Black, releasing it as a single in 1994. Take a listen

6. Symptom of the Universe

How often can you point to a single song that created a genre? In the case of Black Sabbath, there are several individual tracks that were formative and instrumental, but “Symptom of the Universe” is the exact birthplace of thrash metal. The breakdown in the middle with Tony Iommi’s palm-muted alternate picking followed by a screaming solo while Bill Ward plays with both double-time and half-time feel are the blueprint for the entire thrash sound. Showing off their versatility, though, the band pivots into a jam at the end worthy of Zeppelin or the Allmans. One of the leading voices of post-Big Four thrash recorded a tribute in 1994. Listen to Sepultura rip through the song here:

5. Sweet Leaf

If “Symptom of the Universe” invented thrash, then there can be no doubt that “Sweet Leaf” invented stoner rock. Inspired by the old slogan for Sweet Afton cigarettes (“it's the sweetest leaf that gives you the taste”) which were frequently smoked by Butler, the song is an ode to the literal mountains of hashish and cannabis that the entire band was consuming during the recording of Master of Reality. The lyrics are an homage to both the intoxicating effects of the drugs and the inspirational effect it had on the recording sessions. To truly partake of the song in the appropriate way, I had to steal a page from DJ Brilliant and DJ Honeysuckle Vines and present the slowed and reverbed version here:

4. Iron Man

Some people would say that it’s blasphemy that I don’t have this higher in the list, but I would like to remind you that it’s my list and you’re strongly encouraged to make your own. Here’s a link to help you:

For my money, the best Sabbath album is Paranoid, although any of the first six are iconic / epic / amazeballs / whatever the children are using as superlatives these days. “Iron Man” is arguably the most readily identifiable Black Sabbath song to the general public, thanks to its extensive use in all sorts of media. In my mind, the best use of “Iron Man” is obviously the entrance music for Animal and Hawk, the Road Warriors. Let me find a good example of the ferocity that this music inspires:

3. NIB

“N.I.B” doesn’t stand for anything, but elevated fanon says that it’s an abbreviation for “Nativity in Black”. The title actually came from Bill Ward’s goatee at the time, which the rest of the band thought was shaped like a pen nib. Black Sabbath has run with that though, using it as the name of two of their tribute albums and as part of their merchandising. Butler wrote the lyrics for the song, using his Catholic upbringing to inspire a tale of Lucifer himself falling in love and becoming a force for good. The bassline is the dominant factor in the song, laying the foundation for groove metal. (Is there anything that they can’t do?)

2. War Pigs

One of the most stridently anti-war songs in all of popular music, not just the Black Sabbath oeuvre, “War Pigs” began life as a song about witches and pagan rituals. At that time, the title was “Walpurgis”, a reference to the May 1st holiday celebrated by pagans. The record label became uncomfortable with the dark imagery, so the band changed the title to “War Pigs”. It’s been covered by so many artists that it defies numeration, but I’ll add three versions here for variety.

First, there’s the southern rockers Gov’t Mule, joined by Jason Newsted from Metallica and Echobrain on bass:

Then there’s alt-rock weirdos (in the best way) Cake:

And to top it all off, there’s T-Pain, the purveyor of auto-tune who likes to remind people every once in a while that he’s a genuinely talented singer and musician:

1. Paranoid

This is the best Black Sabbath song, off of the best Black Sabbath album. It’s an immense riff, with a tight bassline, nimble drums, and Ozzy’s best vocal performance. Although their debut album was a landmark of hard rock, it’s their second album and its title track where Black Sabbath became themselves. Ironically, it was composed as an afterthought when they needed three minutes of filler. During the recording of the vocals, Ozzy was reading the lyrics off of the sheet Geezer had handwritten just minutes before. Its legacy is untouched, as it appears on best-of lists across all genres and all music publications. It was their first original single in the UK, and remains their only top ten hit. Just listen to it, won’t you?

As a bonus for making it this far, how about a Spotify playlist that covers the era of Black Sabbath that is the topic of this week’s article? Here you go:

I knew that you'd finally end up covering something that I'm really into, we both have broad enough musical interests that there was bound to be some crossover. I'm glad to see that you included "Sweet Leaf" on the list, as I firmly believe that it's the greatest song about weed ever written, which covers a lot of ground. My favorite Sabbath song didn't make the cut though: "Electric Funeral". It has such a crushing and sinister riff, I always felt like it was absolutely begging for a death metal cover. Thankfully Cavalera Conspiracy came close with their cover, giving it that extra dose of heaviness and intensity that I was craving. Clearly Max Cavalera is a diehard fan of early Sabbath.

Cavalera Conspiracy - Electric Funeral

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qFLX_tePN0E

One other thing you might find interesting is the "Sabbath Jam" recorded by the filthy sludge metal lords Eyehategod. Much like Cavalera Conspiracy just cranked up the dial on the impact of "Electric Funeral", Eyehategod did a little medley and showed what happens when you push some of the iconic Sabbath riffs to the limit and just scream your guts out. It rules.

Eyehategod - Sabbath Jam

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kJcUhwCLM7U